DEEMA Al GHUNAIM

Between land and language: an artistic journey of identity and memory

Deema Alghunaim (b. 1984, Kuwait) is an artist whose work explores the tension between language, land, and movement in contemporary settings. She holds a Bachelor’s in Architecture and an MFA from The Ruskin School of Art.

Deema and her daughter Haya near an irrigation canal at Al Ehsa, January 2025 (photo credit: Huda Abdulmughni)

Your work reflects a strong connection to your roots. How has growing up in Kuwait influenced your artistic practices and interests?

I grew up in my father’s library who studied geography in Cairo. The environment strengthened my understanding of the Arabic language as a foundation for learning. I was also raised close to the sea and the desert environment. My father taught us how to shuck pearl oysters and fish, and he showed us the difference between edible sorrel and bitter colocynth. This childhood shaped an empirical view that is sensitive to language and landscape, and became the source of my practice both in art and architecture.

After graduating from architecture school, my father took us on two road trips across the Arabian Peninsula, during which my father explained the land’s topography and transformations while I wrote and photographed. Perceiving the land with my family from a car speeding at 120 kilometers per hour, and understanding the land through the eyes, history, and memories of people, became recurring themes that often occupied my mind and senses. There’s no escaping that in describing the land, you inevitably describe yourself. Moreover, we cannot comprehend the city we inhabit without considering the desert and sea that surround it.

Your father’s stories about life in the region before and after the discovery of oil play a significant role in your work. How do these personal and familial narratives shape your vision and artistic projects?

My father’s stories about the old city and his insistence that we visit what remained of it became a gateway for me to explore its memory and what transpired in the collective consciousness. This is why I became interested in recordings of theater pieces as visual documents of live performances that directly interact with their audience. When I watch an old Kuwaiti play, I compare the era depicted in the performance with the historical transformations within the country. I also observe and question when the audience claps, laughs, and reacts.

I gained a clearer and deeper understanding of the old city when architect Evangelia Ali organized tours that connected the old city to the modern one. Evangelia worked in historical building preservation for the Kuwait Municipality. I remember going on the same tour three times, as if I wanted to absorb everything about it.

My first art exhibition, Tabouq (Bricks), was a photographic work reflecting on the architectural details of 1960s buildings. Shortly after, I was approached by theatre director Sulayman Al-Bassam to collaborate on an adaptation of his play The Speaker’s Progress (the Arabic title is ‘Dar Al Falak’ which roughly translates as life has changed), which narrates a dystopian future where a censored director discovers remnants of a play from the 1960s and attempts to revive it within the restrictions of his time. Although I didn’t fully work on the project, I helped translate two of its three acts. This experience gave me insight into how theatre directors transform and assemble stories through sound and movement.

It sparked in me a new sensitivity to the dimensions of language tied to oral performance—such as tone, gesture, and timing.

Hawalli 8, a piece from Deema’s Tabouq exhibition, 2009.

How do the elements of nature and language interact in your artistic practice?

I have a passion for exploring dictionaries, and the most influential one on my understanding of meanings is Lisān al-‘Arab by Ibn Manzur. This lexicon is known for being arranged alphabetically by the last letter of a word’s root. However, what is even more significant is that Ibn Manzur focused on the language of the Arabian Peninsula in compiling meanings, adding a geographical dimension to the dictionary. Many of the words he explains reflect a direct relationship between humans and their tangible surroundings—land, water, air, plants, and animals. For example, the word “Masafa” which translates in English to "distance," follows the root word "saffa" which translates in English to “to sniff” since the desert travelers used to determine their direction by the scent of the earth. This shows that even the concept of distance, which is considered numerical and abstract, has a tangible, material origin connected to the geography of the place.

This connection has persisted despite political and social transformations, but two main factors disrupted the natural evolution of language: modern urban planning and the forced sedentarization of Bedouins. Both resulted from colonial influences and the discovery of oil in the region.

Urban planning is a spatial form of governance that reshapes the value of land and reorders people’s status within this new arrangement. It also distanced people from the sea, transforming it from a source of livelihood into a poetic idea. The forced settlement or displacement of Bedouins, on the other hand, halted the culture of nomadism.

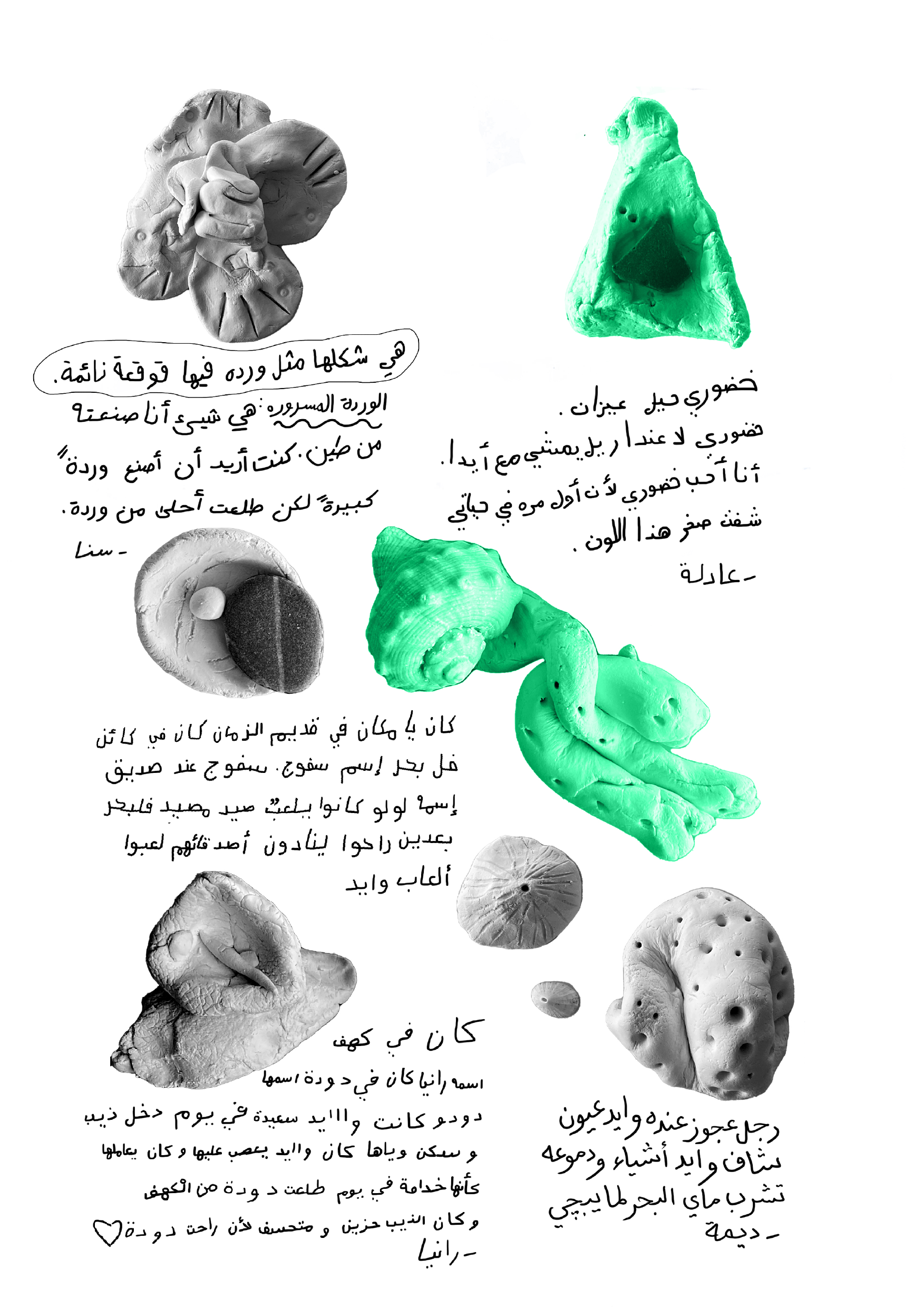

My work and course of action responded to these two themes. I search the land for truffles to envision the future, and I search the language for nodes of becoming. My practice includes improvisational writing, bookmaking, printing, drawing, sculpting, and performance art. Some ideas and emotions become texts, while others take the form of drawings or sculptures.

How can we preserve linguistic heritage in the face of environmental change, urbanization, and technological transformation? What role does the effort to preserve it play?

Preservation is the role of books, while the role of society is to continue using the language. Attempting to understand this language within its modern urban context and comparing it to its historical meanings is a step toward understanding society amidst these changes. The use of language entails the Arab communities to include and consider distinct dialects as a contributing factor in the development of Standard Arabic. This also means that we need to accept the evolution of these dialects. Documenting standard Arabic (Fus’ha) and its fundamentals, and recording dialects and accents at a given time, is urgent, but no less so than allowing the language and its dialects to shape and evolve.

In your MFA thesis, you mentioned that "the inability to capture the present drives you to build a record of future encounters." Can you elaborate on this idea?

The pace of change in this region outstrips efforts of documentation and preservation, making the present a series of fleeting images that shift and transform like a film reel. For this reason, I have come to view documentation as an imaginative act, a space to construct a new relationship with the land—one that is free from the constraints of modern urban networks and unburdened by a nostalgic past that some romanticize.

In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer suggests that we can create a better future for the earth if the creation stories and myths we learn as children reflect a mutual generosity between humans and the land. Inspired by this, I attempt to evoke a future rooted in the celestial stories of the Arab skies, the mountains of the Arabian Peninsula, and the myths of Mesopotamia.

We are accustomed to imagining the future, visualizing it like an image. But perhaps the future is an embryonic sound in the wombs of seashells, the stiffness of bones rubbing against each other, or a cloud of locusts as envisioned by the writer Zakaria Tamer. This is why I love improvisation in every artistic medium I use—it represents the birth of chance and meaningful encounters.

Graphite on paper weave entitled 'A Talisman for Land' displayed at Deema’s MFA Degree Show of the Ruskin School of Art in June 2024

You have a great interest in engaging with children and organic elements. How do these interactions influence your artistic process and outcomes?

Improvisation is about flowing with the stream of thought; it requires a sensitive ear attuned to the stream’s rhythm to improvise effectively. Working with children is the best exercise for sharpening this sensitivity. Listening to a child’s questions revives the surprises of childhood that we don’t want to extinguish within ourselves. It also encourages the child to continue asking questions.

Formal education has conditioned us to seek the "correct" answer, but as Gilles Deleuze explained in his book on Bergsonism, every question inherently carries an answer —once a question is posed, finding an answer is rarely difficult. Therefore, we should teach children how to ask questions just as we teach them how to find answers.

What inspired you to co-found Naktub and focus on producing zines with children? What do you hope to achieve through this program?

The figure of the storyteller has always been vivid in my imagination and the character of Scheherazade, a woman who used storytelling to save herself from death, made me think of stories as shields that protect people from the hardships of life. I started by improvising bedtime stories for my nieces and nephews, then collaborated with my nephew Abdullah and one of our young relatives, who were the most inquisitive, to co-write a story. This experience, along with several simple attempts at writing and illustrating stories for children, evolved into the "Naktub" program, which I co-designed with Lolwa Alkandari in response to the Promenade Cultural Center’s desire to establish a creative writing program in Arabic. It was my friend, Layan Al-Ghossain, who connected me with the center, as she had been conducting creative writing workshops in English with them. It is worth mentioning that this center is part of the Al-Othman family endowment dedicated to supporting culture and the arts in Kuwait.

In "Naktub," (literally translates to ‘We Write’) we work to bridge the gap between formal Arabic and colloquial dialects through artistic forms of expression that rely heavily on language, such as cinema, theater, and music. We place great emphasis on experimentation and reflecting on the tools of writing. For example, we make paper, explore Arabic calligraphy pens, and celebrate mistakes rather than erasing them. We underline them and ponder the new meanings they bring.

We also incorporate the connection between language and environment, hosting elements like the sea or wildflowers to inspire collective writing about these subjects. The collective “we” is always present in this program. While writing is traditionally seen as an individual act, a writer cannot thrive without their surroundings and the characters they encounter in life.

A page from NAKTUB Zine of Fall 2022